By May 1953 the iron keel had been fitted, the hull and canvassed deck painted, the bottom anti-foulinged, the spars varnished and the galvanised rigging treated with rust-preventing fluid. As I recall neither standing nor running rigging needed renewing, while the mainsail and jib were worn but still serviceable. So we were ready for the great day – the launching of a thirty-two year old 6-metre after a long lay up. We had bean warned by friends that she might leak a bit, but we were not prepared for the enormous inrush of water which threatened to sink her alongside the crane jetty. There was frantic activity by yard staff and worried owner to find sawdust, which sprinkled around the hull is supposed to be sucked between the planks and expand, thereby providing ‘instant’ caulking. Whether this palliative works or not I have doubts: I can see that sawdust may fill and caulk seams close to the surface, but how it can reach gaps in the garboards is beyond me. However, by the time Zenith had sunk to a level of half her freeboard the inrush had slowed down, and by the end of the day we were reasonably hopeful that she would remain afloat overnight. Indeed, after pumping out the following morning she was fairly ‘tight’ and within a few days she was as dry as she would ever be without exterior hull treatment.

After a weekend stepping the mast and setting up the rigging we were ready to take to sea. Without an auxiliary engine and with two and a half miles of the River Hamble to navigate before reaching the Solent, we cast off with some trepidation, having first made sure that winds would be light and tidal streams favourable. We need not have worried – Zenith handled like a dinghy responding quickly to helm and sail adjustments. In those days the Hamble had no marinas, very few piles, and only well scattered moorings, so there was plenty of room to tack.

The exciting sailing we enjoyed in the summer and autumn of 1953 gave us plenty of information about the hull and its sailing qualities. Firstly, we found that the iron keel, though it brought her down very close to her marks, altered her centre or lateral resistance very considerably and she had heavy weather helm. Secondly, tne garboards and adjacent planks were visibly opening and closing when under sail in force 4 and over, and we were constantly pumping out. Thirdly, the lightly constructed hull, with only the hog and the deck shelf beams in timber of any real substance, twisted like a racing dinghy when under sail, made clearly visible by the canvassed deck which rucked into a wave formation, running diagonally from bow to stern and changing direction according to tack.

In the late autumn of 1953 we had Zenith lifted out and back under cover in Bursledon Shipyard for fitting out as a cruising yacht. Our plan was simple: to stiffen the hull laterally with three bulkheads, and longitudinally with solid cabin sides, including cockpit coamings and extensions over the foredeck and counter, built from full length mahogany timber. Hours were spent planning the shape of these long members to disguise as far as possible the height of the doghouse coach roof to give standing headroom at the aft end. The foreward bulkhead was placed just in front of the mast with a small door through which we could enter the fo’c’sle by crawling on hands and knees. Here we installed the heads, but even with the coachroof extending forward some three feet we had to built a hatch over to make use of it. The world knew what was going on when a head appeared.

The saloon had two conventional berths at the forward end, running fore and aft, with two folding pipecots for the children. They used these under protest, for they were narrow and uncomfortable, with very little headroom over. In the doghouse there was a quarter berth on the starboard side, running under the cockpit seat. So we could sleep five! An engine box occuped about half the sole in the doghouse, the top serving as a galley working surface. The galley stove was housed on the port side over the engine box, which was itself offset for a shaft passing through the port quarter. Steve was an Austin 7 enthusiast and we found an engine which he marinised very successfully, and which gave a forward speed of 5 knots at half throttle. The engine gave us satisfaction for nearly 18 years with only rare failures. There were, of course, blocks exchanged and re-bores made during this time and I recall searches in scrapyards for suitable magnetos. The gearbox was modified with a system of sprockets and cycle chain which enabled third gear to be used for driving Zenith astern at about 3 1/2 knots. Abaft the engine box was a bulkhead with a central companion way into a fairly spacious cockpit, with the third bulkhead positioned just forward of the rudder post.

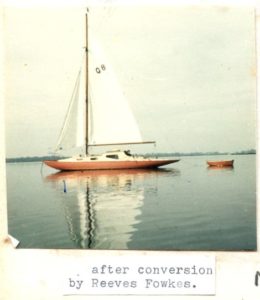

I think our plan was probably as good as it could be, having regard to the shortage of space below decks. Certainly we never made any significant changes to the accommodation. For eighteen years we sailed almost every weekend from April to October and cruised during the summer months, enjoying very happy sailing, some anecdotal incidents, and two major disasters, before parting with Zenith in 1972.